The following article appearswith the kind permission of DEMO – das sozialdemokratische Magazin für Kommunalpolitik and was published in that magazine on 6 July 2021.

DEMO: Mr Seibel, please explain briefly: what exactly is CityLAB Berlin and what is its purpose?

Dr Benjamin Seibel: CityLAB is a public innovation laboratory. “Lab” means we’re experimenting – and we’re doing so at the interface between urban development and digitalization. We’re trying things out to see how technology can make the city a better place to live, while at the same time looking into the challenges that technology involves.

Together with the public administration in Berlin, we carry out innovation projects at both state and district level. But we’re also a public space where a whole range of civil society initiatives, universities and start-ups can get involved. We organize events and workshops on topics such as mobility and sustainability, citizen participation and much more. So we’re a platform where people can exchange ideas on issues, find out information and meet like-minded people, but we also run our own projects.

There’s a lot of talk about the “smart city” in public debate. But it’s not always clear what that means exactly. How do you understand the term and what goals do you believe it involves?

‘Smart city’ is indeed an ambivalent concept that is highly disputed and hotly debated. Everyone has their own slightly different definition of what it actually means. We say that the idea of the ‘smart city’ is more about the ‘how’ than the ‘what’. In other words, how we go about doing projects, how we handle certain developments.

Technology is not an end in itself. But the technical transformation of cities is happening anyway, even without us doing anything about it: there are companies pushing into these markets and it’s becoming more and more natural for citizens to live and work in the digital sphere. The question is: how are the state and the administration handling this? How can developments be shaped to serve the common good? And how should the city and its administration be positioned so as to be able to act on these developments from a position of empowerment? As I see it, ‘smart’ means retaining a certain flexibility and not having to say: we have to bow to constraints. To do this, we need to develop skills, keep in step with practice, and be more exploratory. A digitalization project can’t be planned as they used to plan highways. You have more uncertainty, but you can also modify the process much more easily as you go along, adapting it to new circumstances.

That still sounds quite abstract. Let’s look at some concrete examples. You’re involved in projects such as Gieß den Kiez and Digital vereint. What’s going on with those?

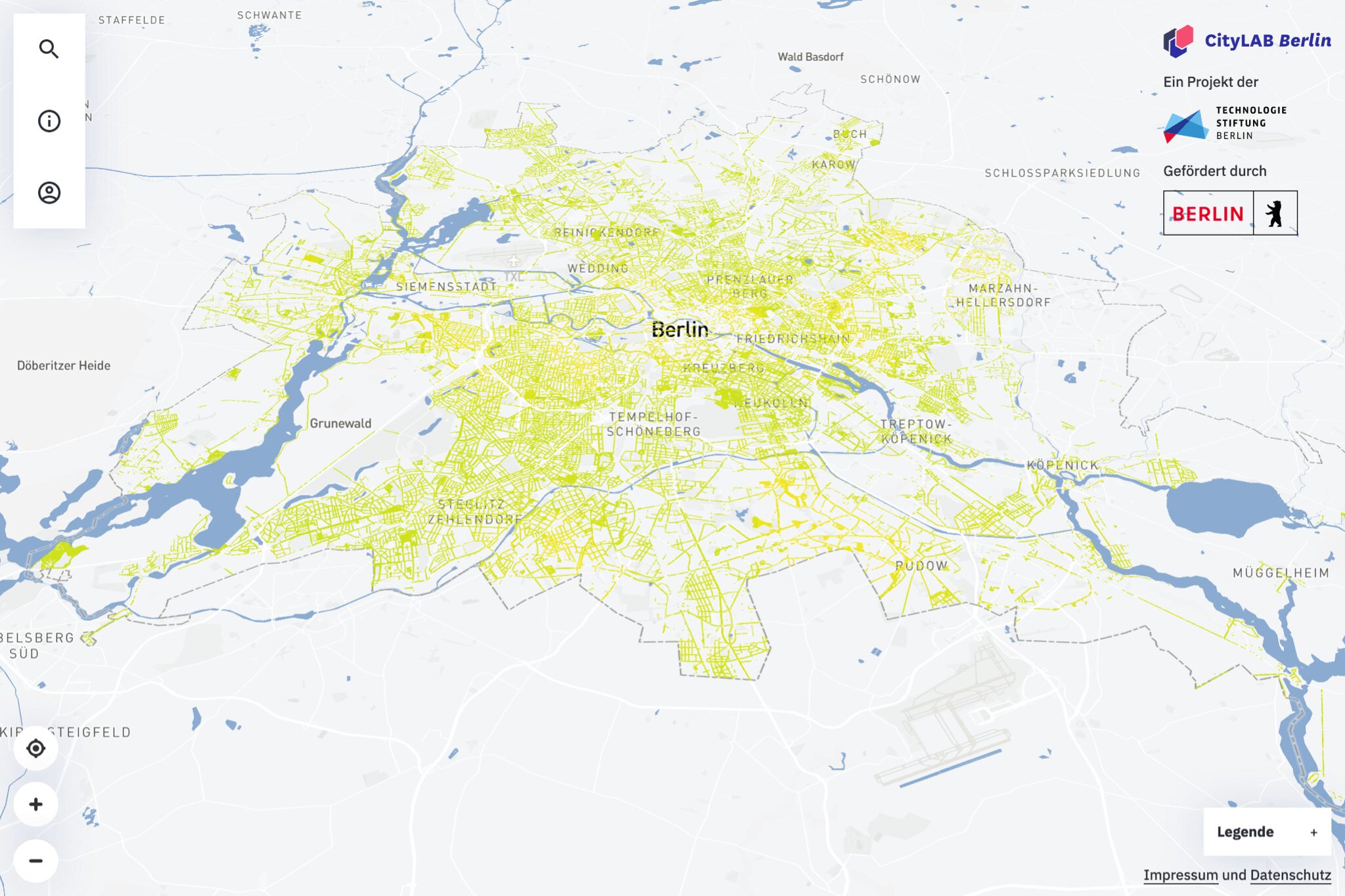

Gieß den Kiez (‘Water your neighborhood’) is a great example of how digitalization can be combined with citizen participation and sustainability. It’s an online map where you can find information about the trees in the city of Berlin and it allows people to record when they’ve watered the trees. The reason behind this is that there are a lot of people in Berlin who care about the city’s trees. Unfortunately, trees in the street suffer a lot from the dry summers caused by climate change. Some of the districts are not keeping up with watering, so a lot of people are committed to preserving the trees on their street themselves. But this all used to happen in a very uncoordinated way. The neighborhood map allows people to record what they’re doing. In this way, other people can see what’s been happening and say: right, this tree was watered yesterday by the neighbor, so I’ll take care of this other tree next to it. The site has several thousand active users, and a real community has developed. We get the data from the Senate Environment Department – they have the trees listed in their geo-information system anyway. Open access was provided for the data so that we could use it to develop the application. This is actually quite typical of the way we work: at the interface between public administration and urban society.

Another project is Digital vereint (‘Digitally united’). The idea for this arose during the pandemic when the question was: what will actually happen to all the associations and volunteers who are now being forced to go digital? We talked to lots of small associations and initiatives, and they told us again and again: we don’t even have the digital infrastructure to continue our work. It starts with mundane things like video calls. A small association usually doesn’t have IT experts. And often, solutions like Zoom are not ideal for small initiatives because of the potential privacy issues and other possible complications. So this question arose: why can’t the city provide infrastructure for its volunteer citizens? And that’s exactly what we’re doing with Digital vereint. Associations can contact us and get access to a free, privacy-friendly video conferencing tool as well as other tools. We operate the infrastructure to support the associations. And we help city stakeholders develop skills by providing workshops and educational activities. Here they can learn the following, for example: How do I deal with social media as an association? What are the data privacy pitfalls to look out for?

On your website it says: digitalization is an opportunity to break down barriers. Can you explain what you mean by this?

Unfortunately, technology often evolves in ways that creates new barriers. One reason for this is that people who are not so tech-savvy tend to get left behind. Our idea is this: that’s not how things have to be! It all depends on how you shape what’s happening.

Example: We have a project going on right now with the Senate Interior Department where we’re looking at the forms used by citizens to apply for things. These processes are now being digitized, too. Our approach was this: we’re not going to digitalize everything 1:1, we’re going to simplify the forms at the same time and make them more user-friendly. We also offer workshops and coaching sessions on simple language: this means that as digitalization progresses, you will also see a simplification of the bureaucratic German language being used. Our idea is this: filling out a form can actually be fun, too. But you mustn’t overwhelm people with technical terms.

We also have projects explicitly on the topic of accessibility, such as Dialogstarter for example. The question here is: how do deaf people get around in the public domain? And how can digital tools or installations in public spaces help facilitate orientation?

Berlin’s administration has a reputation for being somewhat old-fashioned and sluggish. But now they’re looking to experiment and try out new ways of doing things. How does that fit together and how have you experienced working with them?

Our experience has generally been positive, though there are challenges of course. To some extent, the impression of inertia derives from the fact that the Berlin administration has 140,000 employees. A huge tanker is bound to move slowly. But here again, there are lots of motivated and committed individuals who want to make a difference and try out new ways of doing things. They can come to us and they’ll find like-minded people. And collaboration is always voluntary. We’re not an authority: we don’t order people to do things, we offer them things.

People like to call for a cultural change in administration. But what form should that take exactly? Through us, administrative employees can get to know a different approach when they see us using modern tools and design workshops in a more contemporary style, applying new methods and coordinating processes digitally. They then take what they’ve seen back to their workplace with them. If all goes well, this new type of approach is then adopted there, too.

CityLAB is very much focused on Berlin. To what extent can other municipalities benefit from the experience you’re gaining in the capital?

There are lots of other towns and cities that are establishing innovation labs, including smaller municipalities. We’ve set up a network and initiated the event series LabCamp. Here, innovation labs from all over the German-speaking region meet once a quarter to engage in dialogue. Often, these innovation units can feel like lone warriors – so dialogue and knowledge transfer is all the more important.

CityLAB is operated by Technologiestiftung Berlin and is a non-profit institution. The funding comes from the state of Berlin. But there’s no question as far as we’re concerned: since we’re using public funds, we’re going to share our knowledge and the results of our work. Our software projects are all open source, so they can be freely copied and developed. Gieß den Kiez is now available in Leipzig, for example – under the title Leipzig gießt. That’s all part of our vision: When it comes to digitalization, you shouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel all the time. The projects that are going well should be able to be copied and taken forward by other municipalities.